When Relationships Feel Hard: Understanding Relational Strain

Have you ever noticed how some relationships leave you feeling energized, as though the effort required to sustain them carries little lift, while others leave you watching your resources slip steadily through your fingers? With increased experience in polyamory, many people encounter an emerging realization: certain relationships pull on bandwidth far more than others.

You can love someone and choose them deliberately, yet still feel wrung out after every interaction. Even in relationships without obvious dysfunction or open conflict, depletion can linger in the body like background noise that never quite fades.

Why does this happen?

Many people, especially those practicing polyamory or other forms of consensual non-monogamy, struggle to name this experience. They scan for red flags and find none. They inventory logistics and locate nothing particularly unreasonable. The relationship passes every ethical and relational smell test, yet an internal tension persists. Something registers the cost, as the demands of this high-cost relationship push them toward polysaturation more quickly than their other connections.

This article seeks to support you in understanding why some relationships ask more of your resources than others, even when love flows freely.

Bandwidth, Relational Labor, and Relational Strain

Why do some relationships feel so hard, even when love, care, and effort are present?

To understand this, we first need to clarify bandwidth and relational labor. Once we understand those, we can explore relational strain, the pressure that often makes relationships feel exhausting.

Every relationship requires effort directed toward the relationship itself. We call this effort relational labor. Relational labor includes the ongoing emotional, mental, physical, and interpersonal work that sustains connection over time. It shows what work partners actually do to keep their bond alive.

When partners engage in relational labor, they draw from their available bandwidth. Bandwidth consists of finite resources that partners must share across relationships, responsibilities, and life demands.

Bandwidth fuels relational labor. It includes:

emotional capacity for attunement, regulation, and repair

cognitive and logistical capacity

physical energy

time and attention

Because time and energy are finite, bandwidth is inherently limited.

Relational strain emerges when relational labor draws heavily on bandwidth. Strain explains why relational labor can feel costly: why it consumes more energy than expected, distributes unevenly, fails to provide relief, or accumulates without replenishment. This difficulty does not necessarily stem from a lack of effort. Instead, circumstances push the relational system beyond the capacity partners can sustainably supply.

One way to picture this is as a bucket of LEGO bricks.

Each person has a bucket filled with a limited number of bricks. These bricks represent available bandwidth—the energy, attention, and capacity a person can contribute at any given moment. When partners build a relationship together, they each draw bricks from their own bucket to create something shared.

The act of choosing pieces, assembling them, adjusting connections, and fixing unstable sections represents relational labor.

Sometimes, conditions make building harder. The instructions are unclear. Pieces may not fit as expected. An uneven surface may tilt or wobble the foundation. Occasionally, a partner disengages from the process or unintentionally disrupts part of the assembly. Sections collapse repeatedly. In these moments, partners must reuse bricks, supply extra pieces, or rebuild portions multiple times just to keep the structure standing.

This repeated demand on finite resources illustrates relational strain. Partners pull more and more bricks from their bucket to maintain the construction, stretching bandwidth beyond its comfortable limit.

In this analogy:

Bandwidth = capacity (the bricks in the bucket)

Relational labor = effort (the act of building and maintaining the structure)

Relational strain = friction and subsequent increased cost (conditions that require excessive, uneven, or ineffective use of bricks)

Relational strain often appears before people can consciously identify it. Many notice exhaustion, irritability, dread, or shutdown long before they understand what the system is experiencing structurally.

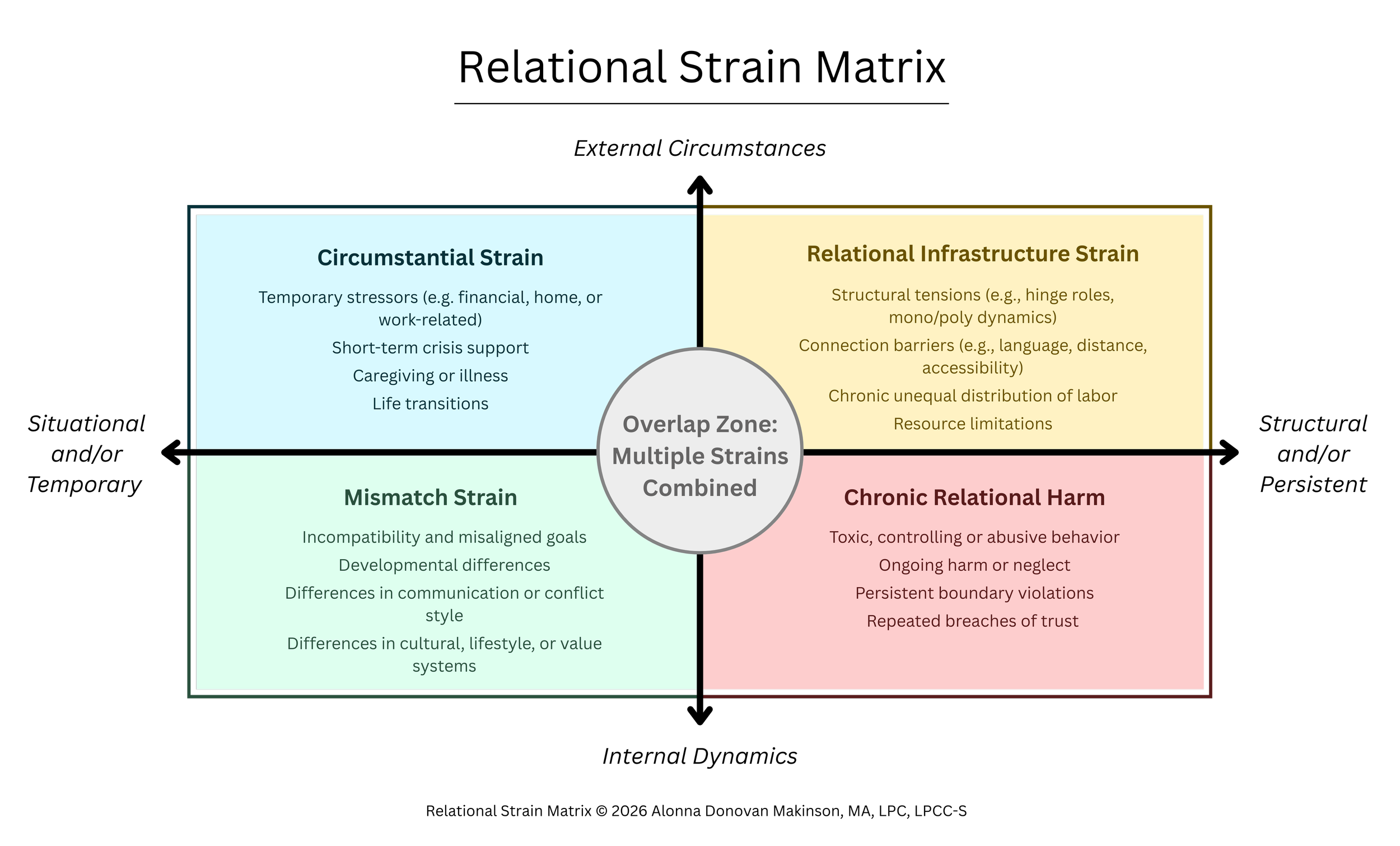

The Relational Strain Matrix

To make sense of relational strain, we use a relational strain matrix. This matrix serves as an orienting map, helping one or all partners notice where pressure arises and why certain patterns feel exhausting. Its purpose centers on illuminating where relational cost comes from and supporting reflection, conversation, and supportive action.

If you recognize one or more of your relationships in one or more areas of the matrix, there’s no need to panic. Relational strain does not signal failure or incompatibility by default. Every committed relationship encounters strain at different points, especially during periods of change, stress, or growth. The matrix exists to normalize that experience and help you understand what kind of pressure is present.

The matrix organizes strain along two axes:

Horizontal axis — Strain Type & Duration

↔ Situational and/or Temporary – Structural and/or Persistent

This axis tracks whether strain comes from short-term circumstances, like a sudden crisis, illness, or caregiving need, or from longer-term, structural conditions, such as chronic role imbalances, ongoing logistical challenges, or systemic stress. Relationships move along this axis as circumstances shift, resources change, or patterns stabilize.

Vertical axis — Source of Strain

↕ External Circumstances – Internal Dynamics

This axis distinguishes whether strain originates outside the relationship, such as from work, family, distance, or societal pressures, or within the relationship, stemming from misaligned goals, differing communication or conflict styles, or repeated boundary challenges. Most relationships experience a mix, moving up and down this axis depending on context.

At the center lies the Overlap Zone, where multiple forms of strain combine and compound, often creating the most noticeable pressure on bandwidth.

Relationships do not remain fixed points on this map. They shift over time as circumstances evolve, resources fluctuate, and relational patterns strengthen or destabilize.

This framework does not intend to tell you what to do or pass judgment on your relationships. It does not function as a scorecard, a diagnosis, or a test of commitment. It also moves away from the idea that trying harder automatically leads to better outcomes.

Instead, the matrix offers a way to trace where relational cost comes from and how it accumulates over time. Rather than prescribing action, it clarifies conditions so choices can emerge with greater awareness and care. Clearer insight into cost and capacity supports decisions that protect both personal wellbeing and relational sustainability.

Orienting to the matrix helps partners identify which pressures operate within the relationship and why capacity may feel stretched thin, even when care and commitment remain strong. Some conditions remain unavoidable, but naming their impact often reduces confusion, softens self-blame, and supports more intentional responses.

Reading the Matrix: Understanding the Terrain of Relational Strain

The matrix contains four quadrants, each reflecting a different pattern of strain shaped by where pressure originates and how long it tends to persist. Some forms of strain arise from temporary, external circumstances. Others take root in ongoing structures, internal dynamics, or repeated patterns of harm. Many relationships encounter more than one of these at the same time.

Each quadrant of the relational strain matrix highlights a distinct way relational cost emerges. Rather than describing relationships themselves, these categories name the conditions that intensify relational labor and accelerate bandwidth depletion.

Top-Left Quadrant: Circumstantial Strain

(External + Often Temporary)

Circumstantial strain arises when external life conditions temporarily increase the cost of staying connected. These strains originate outside the relationship itself and typically carry a clear beginning, middle, and end.

Common sources of circumstantial strain include:

Temporary stressors: short-term pressures that demand extra attention or effort, such as unexpected financial burdens, urgent work deadlines, or home-related challenges.

Short-term crisis support: moments when a partner requires extra emotional or logistical care due to acute events, like an accident, sudden illness, or family emergency.

Caregiving or illness: situations in which one partner must provide additional support to another, a family member, or a dependent, temporarily increasing relational responsibilities.

Life transitions: major changes that disrupt routines or require adaptation, such as moving, starting a new job, graduating, or welcoming a new partner or child into the network.

During these periods, relational labor often intensifies. Partners may offer more emotional support, adjust schedules, take on additional responsibilities, or remain flexible in the face of uncertainty. This increased effort can feel demanding, even while remaining consensual and meaningful.

Circumstantial strain can appear as exhaustion without signaling relational dysfunction. Relationships may continue to function well, communicate effectively, and remain mutually supportive while still demanding more bandwidth than usual. In these moments, strain reflects what life situations require of the relationship, not a problem inherent in the connection itself.

Because circumstantial strain often redistributes labor unevenly, partners may notice temporary imbalances. Once the surrounding circumstances resolve or stabilize, relational cost typically decreases, allowing bandwidth and energy to return to baseline levels.

Top-Right Quadrant: Relational Infrastructure Strain

(External + Often Persistent)

Relational infrastructure strain arises when the underlying systems that support connection place ongoing demand on bandwidth. Unlike circumstantial strain, which comes from temporary pressures, these strains persist until partners intentionally examine, redesign, or adapt to the structures shaping their connection.

This form of strain often appears in relationships shaped by:

Structural tensions: complex network or polycule arrangements, hinge roles, or mono/poly dynamics that create repeated coordination demands.

Barriers to connection: distance, language differences, accessibility challenges, or other external obstacles that require extra planning to maintain engagement.

Resource limitations: chronic constraints on time, energy, or finances that make sustaining relational labor more taxing.

Unequal distribution of relational labor: when certain partners carry more ongoing responsibility for emotional, mental, physical, or logistical work than others.

Under these conditions, the architecture of the relationship itself requires sustained effort for coordination, communication, and repair. Everyday tasks that might feel simple in other contexts, such as aligning schedules, responding to multiple partners’ needs, or resolving minor conflicts, demand extra steps and attention. Even small disruptions can ripple outward, amplifying pressure on bandwidth over time.

Because these demands often feel routine, relational infrastructure strain can hide in plain sight. Partners may normalize ongoing depletion as “just how things are,” especially when the relationship carries deep meaning or aligns with shared values. Yet persistent structural strain continually erodes capacity if left unexamined. Naming this strain allows partners to shift their focus. Instead of asking, “Who needs to try harder?” consider, “Which systems create repeated load, and how might we adjust them or add supports to sustain connection more effectively?”

Bottom-Left Quadrant: Mismatch Strain

(Internal + Variable Persistence)

It is common for partners to have differences and still maintain a healthy, sustainable relationship. Working through these differences can foster growth, alignment, and relational satisfaction. Sometimes that effort strengthens connection and mutual understanding. Other times, fundamental differences remain, and no amount of work fully resolves the friction.

Mismatch strain emerges from differences between partners rather than from external circumstances. These differences do not signal wrongdoing or harm, but instead reflect areas where needs, capacities, or orientations do not align smoothly. Both partners can act with care, good intentions, and commitment, yet still encounter persistent friction.

Common sources of mismatch strain include:

Incompatibility and misaligned goals: differences in relationship goals, timelines, or visions for the future.

Developmental differences: variations in emotional, relational, or life-stage development that shape how partners experience intimacy, independence, or support.

Differences in communication or conflict style: contrasting ways of expressing needs, handling disagreement, or resolving tension, which can lead to repeated misunderstandings despite sincere effort.

Differences in cultural, lifestyle, or value systems: divergence in habits, traditions, moral frameworks, or day-to-day priorities that require repeated negotiation or compromise.

In some cases, partners can soften mismatch strain by engaging the underlying divergence directly through sustained, collaborative effort. This work may include developing clearer agreements, making meaningful compromises, or adjusting expectations in ways that genuinely honor both partners’ needs. When alignment improves at the level of structure or values, relational cost often decreases, allowing capacity to recover.

In other cases, increased relational labor does not reduce cost. Partners may communicate more, compromise frequently, or invest substantial energy into problem-solving without experiencing relief. The effort remains real and intentional, yet strain persists because the work addresses surface symptoms rather than deeper misalignment. Sometimes, non-negotiable needs or values place real limits on what compromise can accomplish.

Mismatch strain can feel especially confusing: love, care, and ethical commitment remain intact, yet friction continues to arise. Over time, repeated effort without resolution may lead to discouragement or depletion, particularly when partners interpret persistence as proof they are failing.

This quadrant encourages reflection on fit rather than fault. Differences between partners do not make anyone “bad” or “wrong.” They may simply signal that the relationship requires more effort than either partner can sustainably provide—or, in some cases, that the cost of continuing exceeds the benefit. Exploring that balance often benefits from support, such as working with a therapist or other trusted professional.

Bottom-Right Quadrant: Chronic Relational Harm

(Internal + Persistent)

Chronic relational harm occupies a distinct quadrant because it operates differently from strain alone. While relational strain describes cost under pressure, harm involves ongoing violation, neglect, or injury within the relationship itself. Harm can manifest across multiple levels—physical, emotional, psychological, spiritual, financial, or social—and often occurs in combination. It also exists on a spectrum: some harmful actions may cause temporary distress or relational disruption, such as occasional breaches of trust, while others create severe danger or ongoing trauma, like stalking, abuse, or coercive control.

Patterns in this quadrant may include:

Toxic, controlling, or abusive behavior: patterns of domination, intimidation, emotional manipulation, or physical aggression that undermine safety, autonomy, or well-being.

Ongoing harm or neglect: repeated or chronic actions (or inactions) that cause emotional, psychological, physical, or social damage, such as consistent disregard for a partner’s needs or safety.

Persistent boundary violations: frequent or repeated disregard for clearly communicated limits, personal space, or agreed-upon rules within the relationship.

Repeated breaches of trust: consistent patterns of dishonesty, secrecy, or betrayal that compromise reliability, accountability, or mutual confidence.

In this quadrant, increased relational labor frequently compounds harm rather than alleviating it. Asking someone to “work harder” under these conditions risks misplacing responsibility and deepening injury. The exception arises when those perpetuating harm take accountability and actively work to change harmful behaviors, ideally with external guidance and structured accountability.

Individuals experiencing chronic relational harm should prioritize safety and resourcing, drawing on trusted networks, professional care, and specialized services as appropriate. Depending on the situation, this might include therapists, domestic violence hotlines or shelters, legal intervention, or law enforcement.

The relational strain matrix separates harm from other forms of strain to guide appropriate responses. While other quadrants invite renegotiation, restructuring, or capacity adjustments, chronic harm calls for protection, accountability, and often separation or outside support. Even so, this quadrant remains part of the matrix because harm draws exponentially on bandwidth, as partners expend resources simply to survive within these conditions.

It’s crucial to underscore that chronic relational harm does not represent “high-cost love” or “difficult seasons.” It reflects a fundamentally different relational reality that demands attention, safety, and appropriate intervention.

The Overlap Zone: When Strain Compounds

While some relationships move predictably across the matrix as circumstances change or resources fluctuate, many experience multiple forms of strain at the same time. Rather than settling neatly into one quadrant, pressures stack, interact, and amplify one another.

For example, a relationship might carry circumstantial strain layered onto relational infrastructure strain, pushing an already taxed system past its sustainable limits. In other cases, mismatch strain may intersect with relational harm, intensifying conditions where increased effort deepens exhaustion or risk. Stressors that feel manageable in isolation can become disproportionately destabilizing when they accumulate.

The Overlap Zone helps explain why relationships can tip into overwhelm without any single issue appearing “bad enough” on its own. Accumulation drives the impact. Each added demand draws from the same finite pool of bandwidth, accelerating depletion even when partners remain caring, communicative, and invested.

This zone calls for a shift in focus. Rather than searching for a single problem to fix, attention turns toward how multiple pressures interact within the relational system. Seeing those interactions more clearly can help partners understand why familiar strategies no longer reduce strain—and why relief may require addressing the broader pattern of compounding demands rather than any one stressor in isolation.

Making Sense of Relational Cost

When relationships feel hard, many people turn inward, questioning their capacity, commitment, or competence. The relational strain framework offers a different lens. Rather than asking, “What’s wrong with us?” it invites a more precise and compassionate question: “What kind of pressure operates here, and what does it cost to respond to it?”

Not all strain signals danger. Not all effort brings relief. And not all depletion means something has gone wrong. At times, strain reflects temporary circumstances that demand more for a season. In other cases, it emerges from structural realities that call for redesign or added support. Sometimes it points toward mismatches that deserve honest reckoning. And in some situations, it reveals harm—conditions where persistence increases risk.

The relational strain matrix does not tell you what to do. It helps you see more clearly. Clarity supports choice—whether that choice involves renegotiating systems, adjusting expectations, seeking support, setting firmer boundaries, or deciding that the cost of continuing exceeds what you can sustainably offer.

Any relational system can benefit from understanding strain, but this framework carries particular relevance for polyamory and other forms of consensual non-monogamy, where care, responsibility, and emotional labor extend across multiple connections. Bandwidth remains finite, no matter how sincere the commitment. Naming strain allows partners to respond intentionally rather than reactively, to preserve connection where possible, and to step away where necessary.

Understanding relational strain often raises bigger questions about capacity, boundaries, and sustainability. Therapy can help you make sense of those dynamics and decide what kind of change, if any, feels right for you. If you’re interested, I offer a free consultation call to explore your goals, answer questions, and see whether therapy together feels like a good fit.